P/Political Creativities (3): Working With Stuff

- Gayle Letherby

- Oct 24, 2017

- 7 min read

In March 2016 Paula Briggs wrote: "As a child when I wasn’t eating, sleeping or at school, I was making. My memories of childhood relate to stuff – smell, material and texture… It feels so fundamentally good and right to use our hands to manipulate materials – to use tools to extend our ability; to put stuff out into the world. The urge to alter our environment is part of our genetic makeup. The skill of making lies latent within all of us" (emphasis added - full piece here)

My memories of my first year at ‘big school’ (1970/1971) – at a comprehensive in Sheffield and the Girls High School (no 11+ exam for me, just a couple of questions on maths and some reading for the Head) in Falmouth – are joyous. In both of these art, music and English were enriching experiences, encouraged beyond the confines of the classroom. I still remember some of the stories and poems I wrote, and the weeks we concentrated on perspective and on silhouettes and profile in the art room convinced me that I was as artistic as the next girl. At the end of a term’s (free) violin classes the patient teacher suggested that perhaps this wasn’t the instrument for me but I was encouraged to continue with music even though my ear was poor. Things changed somewhat the following year and although I remember continued encouragement in English and music the art classes became a boring hour and a bit each week within which we were told to ‘draw your family’, or something similar, with little/no guidance, explanation, encouragement.

After leaving school at 18 with a couple of lacklustre A’ Levels I trained to become a nursery nurse and right from the start I struggled with much of the practical ‘making’ sessions. I’ll never forget the clunky crib mobile I made; the coat hanger was wooden and should have been wire, the star, moon and sun not that well-made or decorated and all hanging at similar lengths. On reflection I think that the D+ received was rather generous.

I remembered these two artistic disappointments recently when reading the following in a media article focused on ‘creative industries’:

"Whenever I hear the phrase “creative industries” I’m always surprised. I ask myself, are there any uncreative industries? If so, how do they survive?…. we have to debunk the notion popularised by Hollywood that the creative artist is cut from a different cloth than normal folk – that creativity is something mysterious, elusive and cannot be taught.

We are not talking about high art, but empowering people to use their imagination. Not everyone can be Mozart, but everyone can sing. I believe everyone is born creative, but it is educated out of us at school, where we are taught literacy and numeracy. Sure, there are classes called writing and art, but what’s really being taught is conformity.

Young children fizz with ideas. But the moment they go to school, they begin to lose the freedom to explore, take risks and experiment"

The author – Tham Khai Meng - continues:

"We spend our childhoods being taught the artificial skill of passing exams. We learn to give teachers what they expect. By the time we get into industry, we have been conditioned to conform. We spend our days in meetings and talk about “thinking outside the box”. But rarely do we step outside it"

Similar issues are raised in the piece I referred to at the beginning of this piece:

We know that creativity is good for the economy too. The UK creative industries generate £84.1bn a year and account for 2.8 million jobs. It’s the fastest-growing sector of the economy....

We work a lot in schools and see 10-year-olds who can’t use scissors. We see art squeezed into obedient slots that require no mess, quick results and easy success. We see children who have never had to solve the problem of a sculpture that doesn’t balance; never had an argument with a lump of stuff; and never learnt the need to rebuild....Somehow, somewhere along the line, making became seen as a “nice” activity, but one we could do without.

So are we really preparing our children for their creative futures? There are so many reasons not to make and we need to talk about them. Let’s get the reasons our children aren’t making out in the open…. If we want a world full of creative, entrepreneurial thinkers, we need to enable and sustain making from a very young age. Not all of us will become sculptors or engineers or designers, but we will become more connected, rounded and creative people.

In two recent blogs here and here I have concentrated on some of the connections between politics and creativity. This included some consideration of different sorts of political writing and on music, comedy and the like. My main focus here obviously is on the making of ‘stuff’. Such activity, and the (political) discussion of it, is not new. During the movement for abolition, sewing circles served as a place for women to exchange ideas and talk about political work:

Sewing Circles are among the best means for agitating and keeping alive the question of anti-slavery…. A friend in a neigboring town recently said to us, “Our Sewing Circle is doing finely, and contributes very much to keep up the agitation of the subject. Some one of the members generally reads an anti-slavery book or paper to the others during the meeting, and thus some who don’t get a great deal of anti-slavery at home have an opportunity of hearing it at the circle”.

And during World War One:

'A grandmother in Belgium knitted at her window, watching the passing trains. As one train chugged by, she made a bumpy stitch in the fabric with her two needles. Another passed, and she dropped a stitch from the fabric, making an intentional hole. Later, she would risk her life by handing the fabric to a soldier—a fellow spy in the Belgian resistance, working to defeat the occupying German force.

...every knitted garment is made of different combinations of just two stitches: a knit stitch, which is smooth and looks like a “v”, and a purl stitch, which looks like a horizontal line or a little bump. By making a specific combination of knits and purls in a predetermined pattern, spies could pass on a custom piece of fabric and read the secret message, buried in the innocent warmth of a scarf or hat'.

There is a gender element here and given that knitting and sewing have traditionally been viewed as women’s work such activities were rejected by some within the suffrage movements. And yet, some suffragettes used needle arts to further their cause, not least to attempt to appear non-threatening to those opposed to their demands who labelled them ‘unwomanly’.

To bring this right up to date the Women’s March in protest against President Trump’s administration was characterised by the hand-knitted ‘pussyhats’ representative of a resurgence in knitting as a political tool.

In recognition of the importance of creativity more generally, the Labour Party remains committed to putting creative subjects back on the school curriculum. In their 2017 general election Manifesto the Party pledged to pump £160 million into improving school arts facilities each year and to set up specialist careers advice services, following a report noting that schools that encouraged more creativity achieved significantly higher grades.

The ‘Creative Sector’ also featured in the manifesto with a commitment for a £1 billion investment to provide better access to cultural institutions and arts education to provide a creative future for all, or to put it another way; ‘culture for the many, not the few’.

Over the last few months I have been experimenting, both within my academic work and with reference to other non-academic activities (including political activism), with making stuff. I owe my renewed engagement with this sort of creativity to the experience I had at a conference I went to earlier in the year –Thinking Through Things – organised by Magali Peyrefitte and Carly Guest.

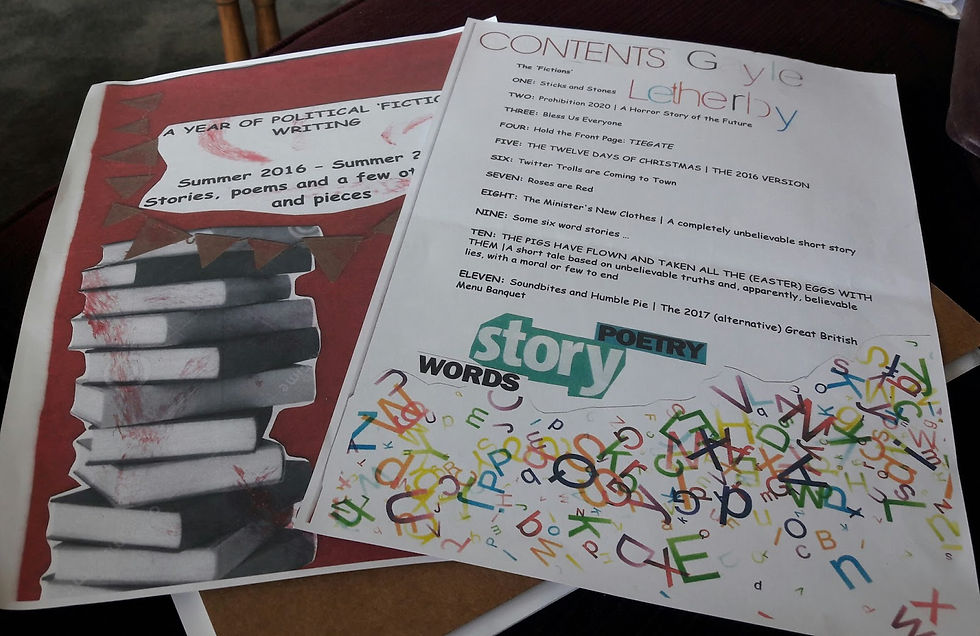

In one of the sessions during the day participants were asked to make a collage representative of their 'work self'. I found this activity and the discussion that took place during it both personally enriching and intellectually stimulating. Since then I have initiated, and been part of, collage and zine (a non-commercial often homemade or online publication usually devoted to a specialised and often unconventional subject matter, sometimes with a political focus) making in several academic settings and created another zine of my own within which I published a series of politically focused short stories that I wrote between the summers of 2016-2017.

This creative doing has surprised me in a couple of ways. First, I was at first amazed at how enjoyable and valuable I, and others I have worked with, found such activity. But after all…to quote Paula Briggs one last time:

"Making connects the hand, eye and brain in a very special way. It’s empowering for both maker and viewer. The act of making is optimistic; it’s an act of faith. People of all ages feel better for doing it. Making can also be very social – conversations can meander while hands are kept busy"

Second, I have wondered why it took me so long to realise the importance and possibilities of such work. Especially as I have long been concerned to encourage those I have had the privilege to teach and mentor to not be frightened of play (as in playing with research data, with method, with theory and with the words we use to write up such endeavours). Perhaps, and I’m trying to excuse myself a little here, my reticence to play with ‘stuff’ is because of my earlier disappointing outputs. Anyways here are some examples (so far):

My first collage: My researcher self

My Most recent collage: My mentor self

For more by this author, visit Gayle Letherby's blog

Comments